Should you use Rust unwrap?

@alexeiboukirev8357 Rust is a gift to the developers. Gifts are meant to be unwrapped.

An interesting discussion started on X about the Cloudflare outage, with some

people linking Rust to it, eg:

The Cloudflare outage was caused by an unwrap()

This is like saying that a gun killed someone… It wasn’t the gun; it was the person who pulled the trigger.

The Cloudflare developers certainly know about the risks of unwrap. The bug

was probably caused by a failed assumption: the config file will fit in

memory.

And even if the developer didn’t know that unwrap can panic:

We can’t blame a tool that is well-documented just because someone misused it.

From: https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/option/enum.Option.html#method.unwrap

Returns the contained [`Some`] value, consuming the `self` value.

Because this function may panic, its use is generally discouraged.

Panics are meant for unrecoverable errors, and

[may abort the entire program][panic-abort].

Instead, prefer to use pattern matching and handle the [`None`]

case explicitly, or call [`unwrap_or`], [`unwrap_or_else`], or

[`unwrap_or_default`]. In functions returning `Option`, you can use

[the `?` (try) operator][try-option].

# Panics

Panics if the self value equals [`None`].

The argument that languages and standard libraries should avoid having constructs that enable bad patterns is actually valid, though.

So lets investigate:

- Use cases for unwrap

- Use of unwrap in important Rust crates

- Would it be better if Rust didn’t have unwrap?

- How could the Cloudflare bug have been avoided?

Use cases for unwrap

It is better to read this post by Andrew Gallant (ripgrep author) first: Using unwrap() in Rust is Okay

It’s a great and comprehensive post.

note: read everything. Initially it seems that he only use unwrap for

tests and documentation, but that is not the case.

Some important points:

If the value is always what the caller expects, then it follows that unwrap() and expect() will never result in a panic. If a panic does occur, then this generally corresponds to a violation of the expectations of the programmer. In other words, a runtime invariant was broken and it led to a bug.

This is starkly different from “don’t use unwrap() for error handling.” The key difference here is we expect errors to occur at some frequency, but we never expect a bug to occur. And when a bug does occur, we seek to remove the bug (or declare it as a problem that won’t be fixed).

Of the different ways to handle errors in Rust, this one is regarded as best practice:

One can handle errors as normal values, typically with Result<T, E>. If an error bubbles all the way up to the main function, one might print the error to stderr and then abort.

One of the most important parts of this approach is the ability to attach additional context to error values as they are returned to the caller. The anyhow crate makes this effortless.

The use cases for unwrap would be:

- tests

- documentation

- runtime invariants

The runtime invariant is what can cause more controversy.

One could ask: if it is guaranteed to have a value/return ok, why is it an

Option or Result?

It’s a great question and it is well explained in So why not make all invariants compile-time invariants?

In essense, in many cases that will lead to much more complex code and lots of duplication.

“recoverable” vs “unrecoverable”

I’ve personally never found this particular conceptualization to be helpful. The problem, as I see it, is the ambiguity in determining whether a particular error is “recoverable” or not. What does it mean, exactly?

I don’t see ambiguity there, and it’s a very important distinction that has to

be made.

Basically: can the program continue working in a valid state?

Until you find a way to recover, it is unrecoverable.

It will depend on the program and its use case.

Use of unwrap in important Rust crates

ripgrep

crates/core/haystack.rs

impl Haystack {

pub(crate) fn path(&self) -> &Path {

if self.strip_dot_prefix && self.dent.path().starts_with("./") {

self.dent.path().strip_prefix("./").unwrap()

} else {

self.dent.path()

}

}

crates/core/main.rs

if let Some(ref mut stats) = stats {

*stats += search_result.stats().unwrap();

}

if matched && args.quit_after_match() {

break;

}

tokio

tokio/src/io/poll_evented.rs

/// Deregisters the inner io from the registration and returns a Result containing the inner io.

#[cfg(any(feature = "net", feature = "process"))]

pub(crate) fn into_inner(mut self) -> io::Result<E> {

let mut inner = self.io.take().unwrap(); // As io shouldn't ever be None, just unwrap here.

self.registration.deregister(&mut inner)?;

Ok(inner)

}

serde

serde/src/private/de.rs

fn deserialize_seq<V>(self, visitor: V) -> Result<V::Value, Self::Error>

where

V: Visitor<'de>,

{

let mut pair_visitor = PairVisitor(Some(self.0), Some(self.1), PhantomData);

let pair = tri!(visitor.visit_seq(&mut pair_visitor));

if pair_visitor.1.is_none() {

Ok(pair)

} else {

let remaining = pair_visitor.size_hint().unwrap();

// First argument is the number of elements in the data, second

// argument is the number of elements expected by the Deserialize.

Err(de::Error::invalid_length(2, &ExpectedInSeq(2 - remaining)))

}

}

serde_derive/src/internals/ctxt.rs

/// Add one of Syn's parse errors./h

pub fn syn_error(&self, err: syn::Error) {

self.errors.borrow_mut().as_mut().unwrap().push(err);

}

clap

https://github.com/clap-rs/clap/blob/8d87e70789ed7832aa93473779d248090712d66b/clap_builder/src/util/flat_map.rs#L172

pub(crate) fn or_insert_with<F: FnOnce() -> V>(self, default: F) -> &'a mut V {

match self {

Entry::Occupied(entry) => &mut entry.v.values[entry.index],

Entry::Vacant(entry) => {

entry.v.keys.push(entry.key);

entry.v.values.push(default());

entry.v.values.last_mut().unwrap()

}

}

}

https://github.com/clap-rs/clap/blob/8d87e70789ed7832aa93473779d248090712d66b/clap_builder/src/util/color.rs#L83

impl std::str::FromStr for ColorChoice {

type Err = String;

fn from_str(s: &str) -> Result<Self, Self::Err> {

for variant in Self::value_variants() {

if variant.to_possible_value().unwrap().matches(s, false) {

return Ok(*variant);

}

}

Err(format!("invalid variant: {s}"))

}

}

reqwest

https://github.com/seanmonstar/reqwest/blob/a2aa5a34e48724be0c1089b0f5afe49b82ece30e/src/async_impl/h3_client/pool.rs#L63

/// Forget the lock and return corresponding Key

fn forget(mut self) -> Key {

// Unwrap is safe because the Option can be None only after dropping the

// lock

self.0.take().unwrap().key

}

Would it be better if Rust didn’t have unwrap?

From the valid use cases above, I think unwrap has its place.

Gemini 3 response:

This is one of the most debated philosophical questions in the Rust community.

The short answer is no. While unwrap is the source of many production crashes, removing it entirely would make the language significantly more frustrating to use and, paradoxically, could lead to messier code.

Here is an analysis of why unwrap exists, why it is dangerous, and why we still need it.

The Case Against unwrap (The “Why it’s bad” view)

If you are asking this, you have likely encountered a production crash caused by a lazy unwrap().

- It abandons Rust’s safety guarantees: Rust’s type system is designed to force you to handle edge cases (

OptionandResult).unwrapis an explicit instruction to the compiler to ignore that safety and crash if things go wrong. - It’s abrupt: It triggers a panic, which unwinds the stack and terminates the thread (or the program). There is no opportunity for recovery.

- It provides no context: When code crashes with

called Result::unwrap() on an Err value, you have no idea why it failed, unlikeexpect("Failed to load config").

The Case For unwrap (Why we need it)

If Rust removed unwrap today, developers would immediately re-implement it. Here are the three scenarios where unwrap is actually the correct tool:

1. Prototyping and Learning

When learning the language or sketching out an algorithm, you don’t want to spend 50% of your time writing error handling boilerplate. You want to see if the logic works. unwrap allows you to defer error handling until the logic is proven.

2. Unit Tests

In a test environment, a panic is exactly what you want. If a setup step returns an error, the test should fail immediately.

#[test]

fn test_calculation() {

// If this fails, the test fails. Perfect usage.

let result = complex_calculation().unwrap();

assert_eq!(result, 42);

}

3. Mathematical Invariants (The “I know better than the compiler” scenario)

Sometimes, you possess logic that the compiler cannot verify. If you are mathematically certain a value cannot be None or Err, handling the error is dead code that clutters the screen.

Example:

// We know "10" is a valid integer.

// Handling the error here would be verbose and pointless.

let number: u32 = "10".parse().unwrap();

In this case, unwrap acts as an assertion. You are telling the compiler: “Trust me. If I am wrong, I deserve to crash.”

The “Better” Alternatives

If you feel the urge to use unwrap, Rust provides alternatives that are almost always better in production code.

1. expect()

This is identical to unwrap, but allows you to provide a custom error message.

- Bad:

file.open().unwrap()(Crashes with generic error) - Better:

file.open().expect("CRITICAL: Configuration file missing")(Crashes with context)

2. The ? Operator (Propagation)

Instead of crashing, pass the problem to the caller.

- Idiomatic:

file.open()?This keeps the current function safe and lets the parent function decide how to handle the failure.

3. unwrap_or / unwrap_or_else

Provide a fallback value instead of crashing.

// If the env var is missing, don't crash; just use port 8080.

let port = std::env::var("PORT").unwrap_or("8080".to_string());

Summary Table: When to use what

| Tool | Behavior | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|

unwrap() |

Panic on failure | Quick scripts, prototypes, unit tests. |

expect() |

Panic with message | When you are 100% sure it won’t fail (Invariants). |

? |

Return error | Production code, libraries, standard logic. |

unwrap_or |

Return fallback | When a default value is acceptable. |

Conclusion

It wouldn’t be better if Rust didn’t have unwrap, because panicking is sometimes the correct response. However, it is better if you use a linter (like Clippy) to forbid unwrap in your production codebase, forcing you to use expect or proper error propagation.

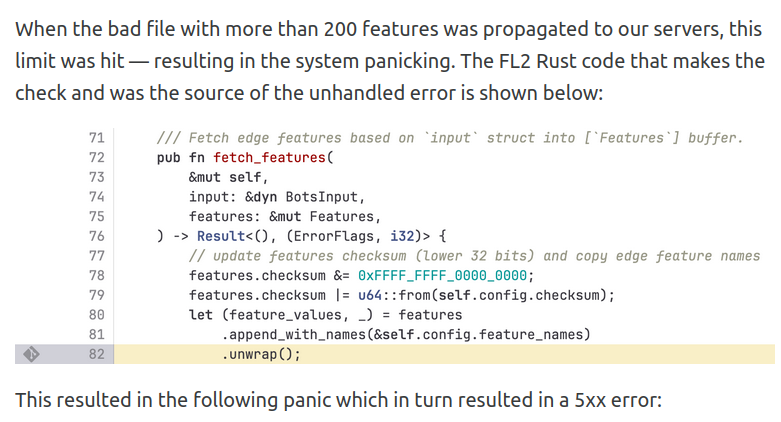

How could the Cloudflare bug have been avoided?

fn fetch_features(..., features: &mut Features)

-> Result<(), (ErrorFlags, i32)> {

...

let (feature_values, _) = features

.append_with_names(&self.config.feature_names)

.unwrap();

}

Possible cases:

append_with_namesreally can’t fail: then it should not return an Option/Result. Callers should not have to think about it. If there is a bug, then it should panic insideappend_with_names.append_with_namescan fail: callers should not useunwrap, and the bad case should be handled properly.append_with_namescan fail, but not at that point: then the assumption failed.

The bug happenned because a bad configuration file was sent to this code.

The root cause was creating and allowing this bad configuration file to spread.

Now the question is: should the Rust code handle that?

Maybe, that’s up to Cloudflare to decide.

As it’s part of a critical system that affects many other companies, it

probably should be handled.

One option might be to accept only the features that fit in the

pre-allocated memory, and log an error or send an alarm if the threshold is hit.

References

Cloudflare outage on November 18, 2025

Richard Feldman: The Cloudflare outage was caused by an unwrap()

Using unwrap() in Rust is Okay

ThePrimeTime - Another Internet outage???

Blessed.rs An unofficial guide to the Rust ecosystem

Appendix A

Miguel Ojeda

Two points, if I may:

- Whether a program is correct or not all depends on the requirements. For instance, a program like fn main() { panic!(); } may be correct if the requirement is that it always panics. For instance, for testing a testing framework.

- Even if “normal” programs are expected to “not panic”, panics can still happen in fully correct programs. For instance, a hardware error that makes an assert fail, even if triggering that assert is impossible given Rust semantics.

In short: if a programmer uses a panic, that just means the program does not have a way to handle the error. Whether that is the right choice, and whether that is an actual bug or not if it happens, and whether abort or unwind should be used, etc., it all depends on the requirements.

# Appendix B

**Prompting Gemini 3: Show me some valid uses of unwrap in important Rust crates**

It is validating to see that even the "gods" of the Rust ecosystem use `unwrap()`. However, they use it very differently than a beginner does.

In high-quality crates, `unwrap()` is rarely used to say "I hope this works." It is used to say **"It is logically impossible for this to fail, and if it does, the world is broken."**

Here are four specific, valid patterns found in major crates.

-----

### 1\. The "Poisoned" Mutex (Standard Library)

This is arguably the most common `unwrap` in production Rust code.

**The Pattern:** Locking a Mutex.

**Where you see it:** Almost every multi-threaded crate (`std`, `tokio`, `actix`).

```rust

use std::sync::{Arc, Mutex};

let data = Arc::new(Mutex::new(0));

// 👇 This is considered idiomatic, valid Rust.

let mut lock = data.lock().unwrap();

Why it’s valid:

Mutex::lock only returns an Err if the previous thread holding the lock panicked (this is called “poisoning”). If a thread crashed while modifying the data, the data is likely corrupted.

- The logic: “If the data is corrupt, I cannot safely continue. Crash this thread too so we don’t spread the corruption.”

2. Static Initialization (Regex / Lazy Static)

The Pattern: compiling a hardcoded string into a complex object during startup.

Where you see it: regex, once_cell, lazy_static.

use regex::Regex;

// We are hardcoding the pattern. We aren't accepting user input here.

let re = Regex::new(r"^\d{4}-\d{2}-\d{2}$").unwrap();

Why it’s valid: The input string is a string literal written by the programmer. It will not change at runtime.

- The logic: “If I made a typo in this regex, the program is fundamentally broken. I want to know immediately (crash on startup) rather than handle a

RegexErrorthat can never happen once the code is correct.”

3. Writing to Memory Buffers (Serde / fmt)

The Pattern: Using the std::fmt::Write trait on a String.

Where you see it: serde_json, log, and formatters.

The Write trait is designed for I/O (files, network), so it returns a Result because disks can be full or networks can disconnect. However, you can also implement Write for a standard String (RAM).

use std::fmt::Write;

let mut buffer = String::new();

// We are writing to RAM, not a disk.

// The only way this fails is OOM (Out of Memory), which aborts anyway.

write!(&mut buffer, "Hello {}", "World").unwrap();

Why it’s valid:

Writing to a String in memory does not produce I/O errors. The Result is a formality of the Trait signature.

- The logic: “I am writing to a variable in RAM. There is no disk to fail. Handling this error is dead code.”

4. Proven Invariants (Internal Logic)

The Pattern: You have checked a condition explicitly, so the subsequent operation is guaranteed.

Where you see it: crossbeam, rand, Vec implementations.

Imagine you have a logic flow where you check a queue size.

// Simplified logic often found in channel implementations

if let Some(item) = queue.pop() {

// We just proved 'item' exists.

process(item);

} else {

// ...

}

// But sometimes, the check is separated:

if queue.is_empty() {

return;

}

// We checked is_empty() above.

// We know pop() returns Some().

let item = queue.pop().unwrap();

Why it’s valid: The compiler’s borrow checker is smart, but it isn’t omniscient. Sometimes you (the human) know the state of the system better than the compiler.

- The logic: “I have structurally guaranteed this value exists. The

Nonecase is unreachable code.”

Summary: The Difference is Intent

When a beginner uses unwrap:

“I’m too lazy to handle the error right now.”

When a library author uses unwrap:

“I have proven that this error is impossible, or if it happens, the program is in a fatal state.”