My notes and transcriptions from: The Java Language Environment - A White Paper

https://www.stroustrup.com/1995_Java_whitepaper.pdf

The paper is from October, 1995

My notes start with note:, otherwise it’s from the paper.

The Better Way is Here Now

Imagine, if you will, this development world…

- Your programming language is object oriented, yet it’s still dead simple.

- Your development cycle is much faster because Java is interpreted. The compile-link-load-test-crash-debug cycle is obsolete—now you just compile and run.

- Your applications are portable across multiple platforms. Write your applications once, and you never need to port them—they will run without modification on multiple operating systems and hardware architectures.

- Your applications are robust because the Java run-time system manages memory for you.

- Your interactive graphical applications have high performance because multiple concurrent threads of activity in your application are supported by the multithreading built into Java environment.

- Your applications are adaptable to changing environments because you can dynamically download code modules from anywhere on the network.

- Your end users can trust that your applications are secure, even though they’re downloading code from all over the Internet; the Java run-time system has built-in protection against viruses and tampering.

Beginnings of the Java Language Project

Design and architecture decisions drew from a variety of languages such as Eiffel, SmallTalk, Objective C, and Cedar/Mesa. The result is a language environment that has proven ideal for developing secure, distributed, network-based end-user applications in environments ranging from networked-embedded devices to the World-Wide Web and the desktop.

Architecture Neutral and Portable

The architecture-neutral and portable language environment of Java is known as the Java Virtual Machine.

Design Goals

Simplicity

Programmers familiar with C, Objective C, C++, Eiffel, Ada, and related languages should find their Java language learning curve quite short—on the order of a couple of weeks.

Character Data Types

Java language character data is a departure from traditional C. Java’s char data type defines a sixteen-bit Unicode character. Unicode characters are unsigned 16-bit values that define character codes in the range 0 through 65,535.

Unsigned (logical) right shift

All the familiar C and C++ operators apply. Because Java lacks unsigned data types, the operator has been added to the language to indicate an unsigned (logical) right shift.

note: The sign bit becomes 0, so the result is always non-negative.

jshell -1 1

$1 == 2147483647

jshell Integer.MAX_VALUE

$2 == 2147483647

jshell 1 1

$3 == 0

jshell Integer.toBinaryString(-1 1)

$4 == "1111111111111111111111111111111" // 31 bits

jshell Integer.toBinaryString(-1)

$5 == "11111111111111111111111111111111" // 32 bits

jshell Integer.toBinaryString(-2)

$9 == "11111111111111111111111111111110"

jshell Integer.toBinaryString(Integer.MIN_VALUE)

$6 == "10000000000000000000000000000000" // 32 bits

jshell Integer.MIN_VALUE

$10 == -2147483648

jshell Integer.MAX_VALUE + 1

$11 == -2147483648

jshell Integer.MAX_VALUE + 1 == Integer.MIN_VALUE

$12 == true

jshell -5 2

$13 == 1073741822

jshell Integer.toBinaryString(-5)

$14 == "11111111111111111111111111111011" // 32 bits

jshell Integer.toBinaryString(-5 2)

$15 == "111111111111111111111111111110" // 30 bits

jshell Integer.toBinaryString(-5 3)

$20 == "11111111111111111111111111111" // 29 bits

Arrays

In contrast to C and C++, Java language arrays are first-class language objects. An array in Java is a real object with a run-time representation. You can declare and allocate arrays of any type, and you can allocate arrays of arrays to obtain multi-dimensional arrays.

You declare an array of, say, Points (a class you’ve declared elsewhere) with a

declaration like this:

Point myPoints[];

This code states that myPoints is an uninitialized array of Points. At this

time, the only storage allocated for myPoints is a reference handle. At some

future time you must allocate the amount of storage you need, as in:

myPoints = new Point[10];

The C notion of a pointer to an array of memory elements is gone, and with it, the arbitrary pointer arithmetic that leads to unreliable code in C. No longer can you walk off the end of an array, possibly trashing memory and leading to the famous “delayed-crash” syndrome, where a memory-access violation today manifests itself hours or days later. Programmers can be confident that array checking in Java will lead to more robust and reliable code.

Multi-Level Break

Use of labelled blocks in Java leads to considerable simplification in programming effort and a major reduction in maintenance.

Memory Management and Garbage Collection

Explicit memory management has proved to

be a fruitful source of bugs, crashes, memory leaks, and poor performance.

Java completely removes the memory management load from the programmer.

C-style pointers, pointer arithmetic, malloc, and free do not exist. Automatic

garbage collection is an integral part of Java and its run-time system. While Java

has a new operator to allocate memory for objects, there is no explicit free

function. Once you have allocated an object, the run-time system keeps track of

the object’s status and automatically reclaims memory when objects are no

longer in use, freeing memory for future use.

The Java memory manager keeps track of references to objects. When an object has no more references, the object is a candidate for garbage collection.

The Background Garbage Collector

The Java garbage collector achieves high performance by taking advantage of the nature of a user’s behavior when interacting with software applications such as the HotJava browser. The typical user of the typical interactive application has many natural pauses where they’re contemplating the scene in front of them or thinking of what to do next. The Java run-time system takes advantage of these idle periods and runs the garbage collector in a low priority thread when no other threads are competing for CPU cycles.

note: This is an interesting part, because here he’s targeting interactive applications.<br Ok, but this idle period is sometimes non-existent or very rare for many non-interactive applications, then I language with a garbage collector would not be the best approach.

No More Typedefs, Defines, or Preprocessor

Source code written in Java is simple. There is no preprocessor, no #define and related capabilities, no typedef, and absent those features, no longer any need for header files. Instead of header files, Java language source files provide the definitions of other classes and their methods.

A major problem with C and C++ is the amount of context you need to understand another programmer’s code: you have to read all related header files, all related #defines, and all related typedefs before you can even begin to analyze a program. In essence, programming with #defines and typedefs results in every programmer inventing a new programming language that’s incomprehensible to anybody other than its creator, thus defeating the goals of good programming practices.

In essence, programming with #defines and typedefs results in every programmer inventing a new programming language that’s incomprehensible to anybody other than its creator, thus defeating the goals of good programming practices.

note: I really like James Gosling approach to simplicity, and Java being simple for sure is one of the reasons of its success.

No More Goto Statements

As mentioned above, multi-level break and continue remove most of the need for goto statements.

Object Technology in Java

To be truly considered “object oriented”, a programming language should support at a minimum four characteristics:

- Encapsulation: implements information hiding and modularity (abstraction)

- Polymorphism: the same message sent to different objects results in behavior that’s dependent on the nature of the object receiving the message;

- Inheritance: you define new classes and behavior based on existing classes to obtain code re-use and code organization

- Dynamic binding

Classes

A class is a software construct that defines the instance variables and methods of an object. A class in and of itself is not an object. A class is a template that defines how an object will look and behave when the object is created or instantiated from the specification declared by the class.

Subclassing enables you to use existing code that’s already been developed and, much more important, tested, for a more generic case. You override the parts of the class you need for your specific behavior. Thus, subclassing gains you reuse of existing code—you save on design, development, and testing. The Java run-time system provides several libraries of utility functions that are tested and are also thread safe.

Access Control

When you declare a new class in Java, you can indicate the level of access permitted to its instance variables and methods. Java provides four levels of access specifiers. Three of the levels must be explicitly specified if you wish to use them. They are public, protected, and private.

The fourth level doesn’t have a name—it’s often called “friendly” and is the access level you obtain if you don’t specify otherwise. The “friendly” access level indicates that your instance variables and methods are accessible to all objects within the same package, but inaccessible to objects outside the package.

Abstract Classes

note: with the Java 8 inclusion of default methods in interfaces, the difference between abstract classes and interfaces blurred a little.

So instead of quoting the paper, I’ll quote from https://docs.oracle.com/javase/tutorial/java/IandI/abstract.html

Abstract Classes Compared to Interfaces

Abstract classes are similar to interfaces. You cannot instantiate them, and they may contain a mix of methods declared with or without an implementation. However, with abstract classes, you can declare fields that are not static and final, and define public, protected, and private concrete methods. With interfaces, all fields are automatically public, static, and final, and all methods that you declare or define (as default methods) are public. In addition, you can extend only one class, whether or not it is abstract, whereas you can implement any number of interfaces.

Which should you use, abstract classes or interfaces?

-

Consider using abstract classes if any of these statements apply to your situation:

- You want to share code among several closely related classes.

- You expect that classes that extend your abstract class have many common methods or fields, or require access modifiers other than public (such as protected and private).

- You want to declare non-static or non-final fields. This enables you to define methods that can access and modify the state of the object to which they belong.

-

Consider using interfaces if any of these statements apply to your situation:

- You expect that unrelated classes would implement your interface. For example, the interfaces Comparable and Cloneable are implemented by many unrelated classes.

- You want to specify the behavior of a particular data type, but not concerned about who implements its behavior.

- You want to take advantage of multiple inheritance of type.

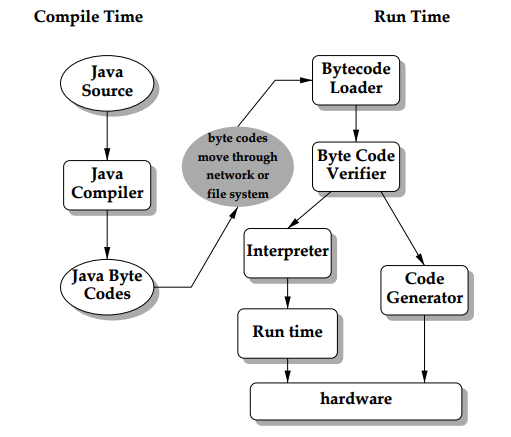

Byte Codes

Java bytecodes are designed to be easy to interpret on any machine, or to dynamically translate into native machine code if required by performance demands.

Java eliminates the portability issue in C and C++ by defining standard behavior that will apply to the data types across all platforms. Java specifies the sizes of all its primitive data types and the behavior of arithmetic on them. Here are the data types:

byte 8-bit two’s complement

short 16-bit two’s complement

int 32-bit two’s complement

long 64-bit two’s complement

float 32-bit IEEE 754 floating point

double 64-bit IEEE 754 floating point

char 16-bit Unicode character

Interpreted and Dynamic

The notion of a separate “link” phase after compilation is pretty well absent from the Java environment. Linking, which is actually the process of loading new classes by the Class Loader, is a more incremental and lightweight process.

The Byte Code Verification Process

The Java run-time system doesn’t trust the incoming code, but subjects it to bytecode verification.

The tests range from simple verification that the format of a code fragment is correct, to passing each code fragment through a simple theorem prover to establish that it plays by the rules:

- it doesn’t forge pointers,

- it doesn’t violate access restrictions,

- it accesses objects as what they are (for example, InputStream objects are always used as InputStreams and never as anything else).

note: there’s probably a bit overhead with this runtime verification, but it’s likely done only once.

The Byte Code Verifier

By the time the bytecode verifier has done its work, the Java interpreter can proceed, knowing that the code will run securely. Knowing these properties makes the Java interpreter much faster, because it doesn’t have to check anything. There are no operand type checks and no stack overflow checks. The interpreter can thus function at full speed without compromising reliability.

Integrated Thread Synchronization

If you wish your objects to be thread-safe, any methods that may change the values of instance variables should be declared synchronized. This ensures that only one method can change the state of an object at any time. Java monitors are re-entrant: a method can acquire the same monitor more than once, and everything will still work.

Performance

new Object 119,000 per second

new C() (class with several methods) 89,000 per second

o.f() (method f invoked on object o) 590,000 per second

o.sf() (synchronized method f invoked on object o) 61,500 per second

note: I wonder how theses numbers are today.

Other interesting observation is synchronized method calls are much slower!

Thus, we see that creating a new object requires approximately 8.4 μsec, creating a new class containing several methods consumes about 11 μsec, and invoking a method on an object requires roughly 1.7 μsec.

While these performance numbers for interpreted bytecodes are usually more than adequate to run interactive graphical end-user applications, situations may arise where higher performance is required. In such cases, the Java bytecodes can be translated on the fly (at run time) into machine code for the particular CPU on which the application is executing. For those accustomed to the normal design of a compiler and dynamic loader, this is somewhat like putting the final machine code generator in the dynamic loader.

The bytecode format was designed with generating machine codes in mind, so the actual process of generating machine code is generally simple. Reasonably good code is produced: it does automatic register allocation and the compiler does some optimization when it produces the bytecodes.

Performance of bytecodes converted to machine code is roughly the same as native C or C++.

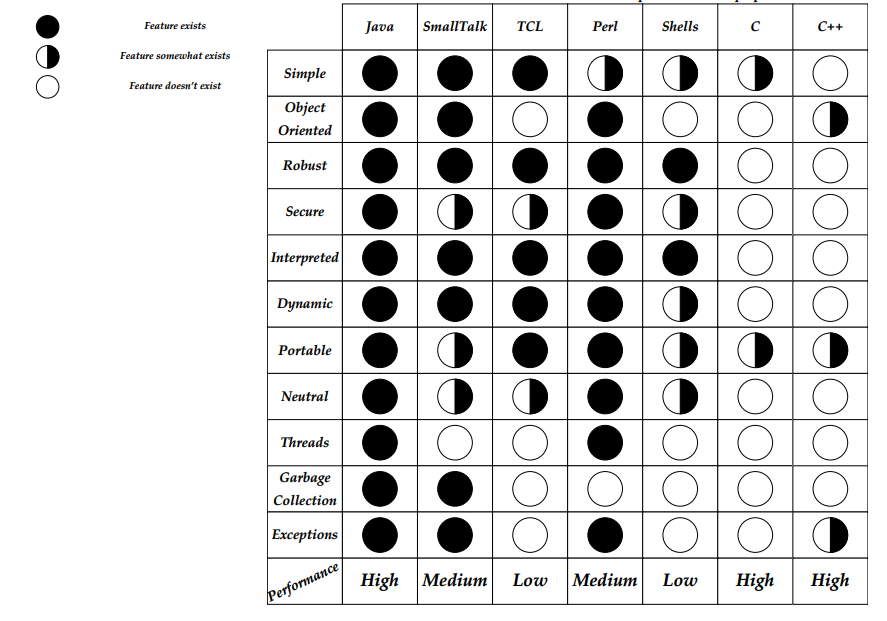

The Java Language Compared

The Java language environment creates an extremely attractive middle ground between very high-level and portable but slow scripting languages and very low level and fast but non-portable and unreliable compiled languages. The Java language fits somewhere in the middle of this space. In addition to being extremely simple to program, highly portable and architecture neutral, the Java language provides a level of performance that’s entirely adequate for all but the most compute-intensive applications.